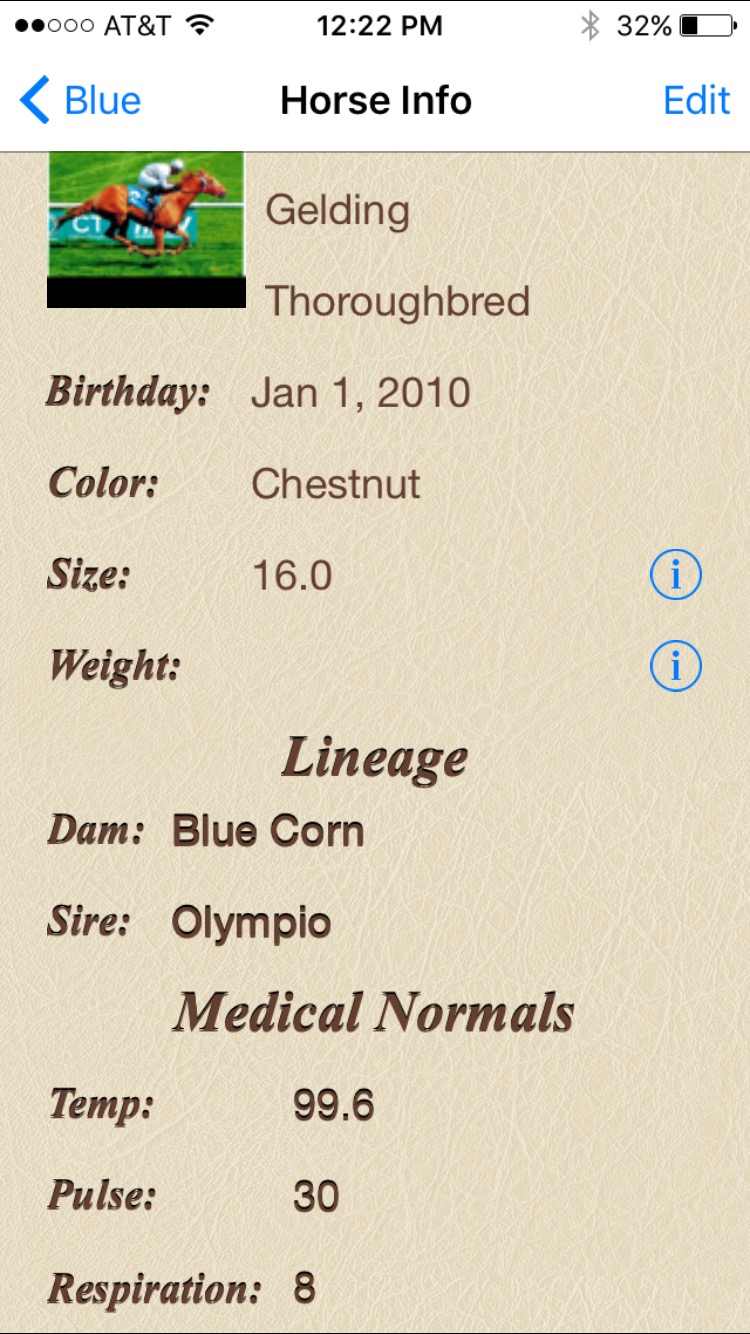

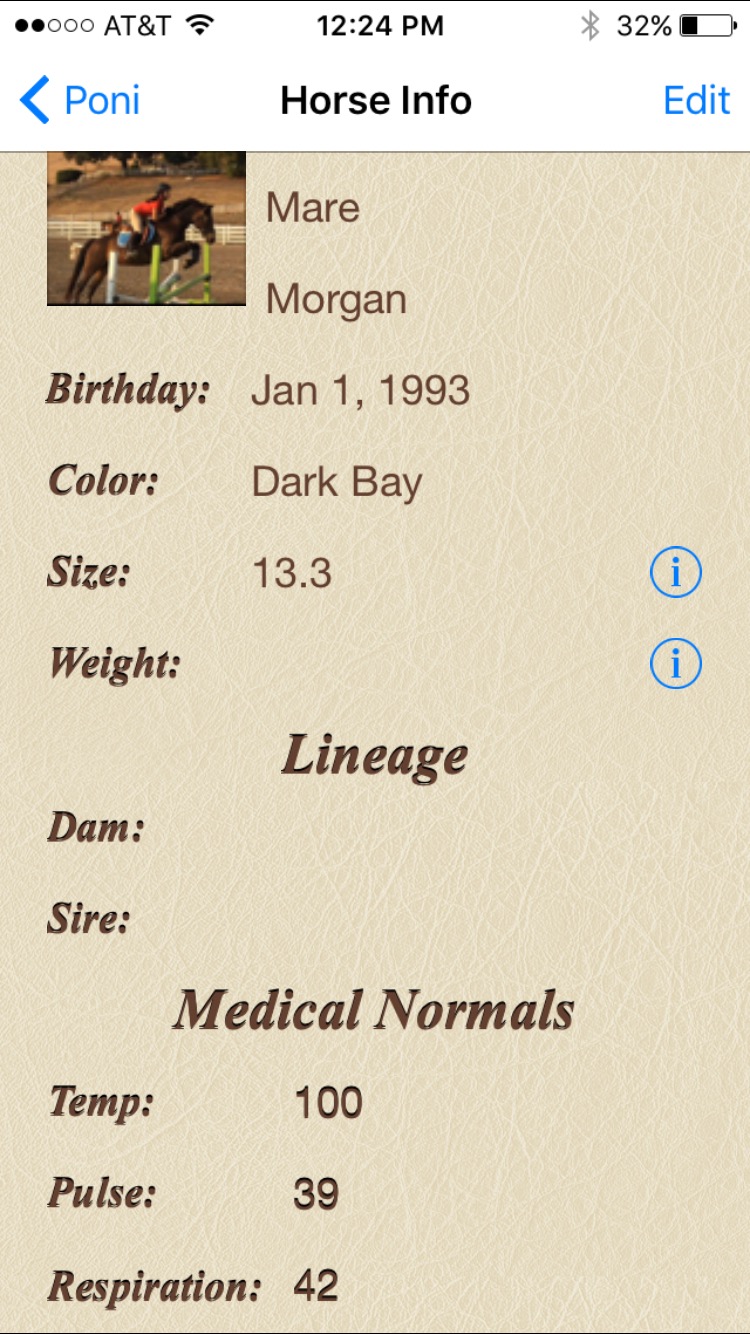

Blue and Corny are the two geldings I’m hoping to take to the 2017 thoroughbred makeover in Kentucky. This blog is documenting our journey together.

These full brothers are owned by a lovely couple that is fairly new to horses. Up to now, they were not involved in any horse management decisions. It’s a big change from racehorse life to bring a sport horse prospect. Some changes have to be made, or at least assessed. The brothers came in to training with me on November 2. Here’s what we’ve done in the first month to support their transition from ex-racehorse, to sport horse prospect.

Housing

The brothers shared a paddock at the farm where they were let down after race training. Their owner, Ann, said that they were bonded and wanted them to stay close to each other. She selected adjacent stalls at Indian Hills so they could maintain their relationship as bffs.

The first day I worked with the horses it became clear that they were too attached to one another. They would be fidgety and anxious without their brother near by. They would call for each other. In general, they were not pleasant to be around.

Anxious over his brother leaving him, Blue began to weave in the cross ties

Anxious over his brother leaving him, Blue began to weave in the cross ties

While I prefer for horses to live in pasture 24/7, these horses have good reasons to be in stalls. Their owners are beginners and want to learn how to handle and care for them. I’m not about to send a beginner in his/her 60s with a bad back out to catch their young ex racehorse in a muddy cliff-side pasture. Maybe later, but not today.

So I decided to keep the brothers in stalls, but move one of them three stalls down. Ann was concerned that Corny would work himself up too much being separated from Blue. I assured her that I would watch him for several hours to make sure he calmed down. Mark encouraged Ann to trust the trainer and to do what I say. Hooray for Mark!

Corny had settled by the end of dinner time, and their separation anxiety drastically deminished over the next week.

Feed

The brothers were currently eating only alfalfa hay and some type of stable mix pellet. Holy smokes! I want to live through training these horses, and I want them to live as well.

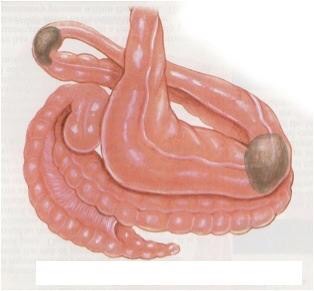

100% alfalfa hay is not a recommended diet. Nutritionists know it doesn’t provide enough fiber top meet a horse’s daily requirements. It also has an inverse calcium to phosphorus ratio, which is linked to developmental bone disorders. Furthermore, alfalfa hay has been linked to the formation of enteroliths in thoroughbreds. No thank you!

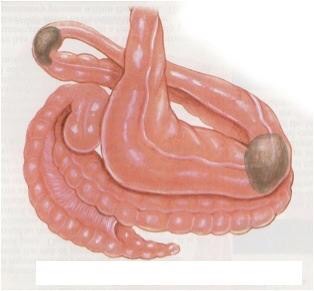

Enteroliths in the GI system of a horse. If these cause discomfort to the horse, they must be removed surgically.

Enteroliths in the GI system of a horse. If these cause discomfort to the horse, they must be removed surgically.

People like to feed alfalfa because it is a high energy feed, and helps put a nice top line on a horse. For a racehorse, I get it, they need lots of energy. Right now, the benefits of alfalfa don’t out weigh the risks for Blue and Corny.

So I made a plan to switch them to all the grass hay they will eat over the course of two weeks. After about three weeks we are now adding in triple crown complete to balance their diets.

Turnout

I can only work with the horses three times per week. That’s not enough time out of the stall for any horse. I signed the horses up for daily turnouts.

While they are on dry lots, they don’t get the benefits of grazing, but they have reportedly been moving around and playing quite a bit. Turnout is crucial to every horse’s mental health.

Blanketing

I’m generally in favor of horses going naked if they can. However, the chestnut thoroughbred is not known for its lush winter hair coat. I don’t intend to clip the brothers this year, but I still wanted them to have blankets. Why?

- Horses generate body heat via movement. This is hard to do in a stall.

- They live in the coldest stalls on the property. Indian Hills Ranch is situated in the hills just above the southern tip of the San Francisco bay. We can count on a cold breeze coming up from the bay every evening. It’s great in the summertime, but can make for some chilly winter nights.

- Horses generate heat via digestion. Grazing horses always have good in their bellies to digest and generate heat. The brothers are getting hay twice a day, and typically finish dinner before the sun sets.

Deworming

*Getting up on my soap box* The American Association of Equine Practitioners no longer recommends rotational deworming. Instead, they recommend bi-annual fecal egg counts to determine what sort of parasites a horse is carrying and performing targeted deworming. You can read about their recommendations here. I’m not going to argue with a bunch of vets, so that’s what I do. *Down from my soap box*

I was able to send fecal samples out for Corny and Blue in their first week, both came back negative.

More poop

I also did a fecal float to determine if the horses were carrying sand in their gut. Blue had a mild colic there week before, so it seemed prudent to check it out.

The way I do a fecal float is to put on a rectal sleeve, pick up a big handful of fecal balls, then invert the sleeve. Then I fill the sleeve with enough water to float the fecal balls above the fingers of the glove. I hang it on a railing for about half an hour. If I can feel sand in the fingertips of the glove after that time, I do a course of psyllium.

Monster Hands! Just kidding, these are fecal floats in progress.

Monster Hands! Just kidding, these are fecal floats in progress.

Blue didn’t have any sand in his glove. Corny had a little bit, so we are going to do psyllium for him.

We can still optimize their health a bit more, but this is what we did on week one. Look for “Management Strategies, part 2” in a week or so.

———

After publishing this post on Facebook, it received this comment from my friend Dr. Clair Thunes. Clair is an independent equine nutritionist and an industry expert in her field.

From Dr. Thunes:. Love the fact that you mentioned that horse sin stalls can be colder than out. Something a lot of people just don’t realize. They assume because they are inside they must be warmer! I’m not sure that meal feeding hay really makes a huge difference in heat generation vs constant grazing because hay stays in the hindgut where it is fermented for over 24 hours so it is being fermented constantly and thus constantly generating heat. It is a good argument though for feeding more hay and less grain in winter. I often hear people say that they feed alfalfa in the winter when it is cold because of the higher fiber but this isn’t true. While alfalfa has plenty of fiber just as much as grass hay, it is higher calorie pound for pound over grass hay so you are feeding more calories when you feed alfalfa vs grass hay and this helps them maintain more weight in cold weather. From the perspective of causing more fermentation there is no reason to feed alfalfa over grass hay. It is interesting that these boys were on 100% alfalfa because most race horses are fed 0% alfalfa only timothy. I suspect this was done for their let down and most likely to reduce risk of ulcers and possibly as a way to get more calories in to them while not feeding much grain.

Yup, Corny is bleeding from his foot.

Yup, Corny is bleeding from his foot.